Reach the bend of the Grand Canal by gondola and catch a glimpse of a sparkling modernist facade between the Gothic windows. Leave St. Mark's Square behind and meet a mighty congress center with essential volumes, or reach, at the end of the Cannaregio district, a new hospital jutting out over the lagoon. The history of twentieth century architecture in Venice is first and foremost (though not only) a story of projects that have never been realized. A different idea of Venice, whose thread has gradually detached itself from reality to design a counterfactual city.

Since World War II, a few attempts were made to give new life and a more contemporary look to the city: Carlo Scarpa, Vittorio Gregotti, and lately David Chipperfield, Santiago Calatrava, Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhas restored pre-existing buildings and built new ones. Still, a lot of architectural potential remained unexpressed. Architects and designers such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn worked on projects with the idea of translating into reality the need for innovation, integrating new structures in the Venetian topography.

Louis Kahn and Venice

The relationship between Louis Kahn (b. 1901) and Venice dates back to 1928, when he visited the city for the first time, and continued throughout his life, consolidating thanks to collaborations with Carlo Scarpa, with the Venice Biennale, a series of courses and, obviously, the project for the Palazzo dei Congressi. Louis Kahn loved the lagoon city, which he defined “a pure miracle”, and always maintained a special link to Venice, creating bonds with some distinguished inhabitants of the city. In 1968 he was invited to present a project for a Palazzo dei Congressi (congress palace) inside the Biennale gardens, where he had already exhibited his work.

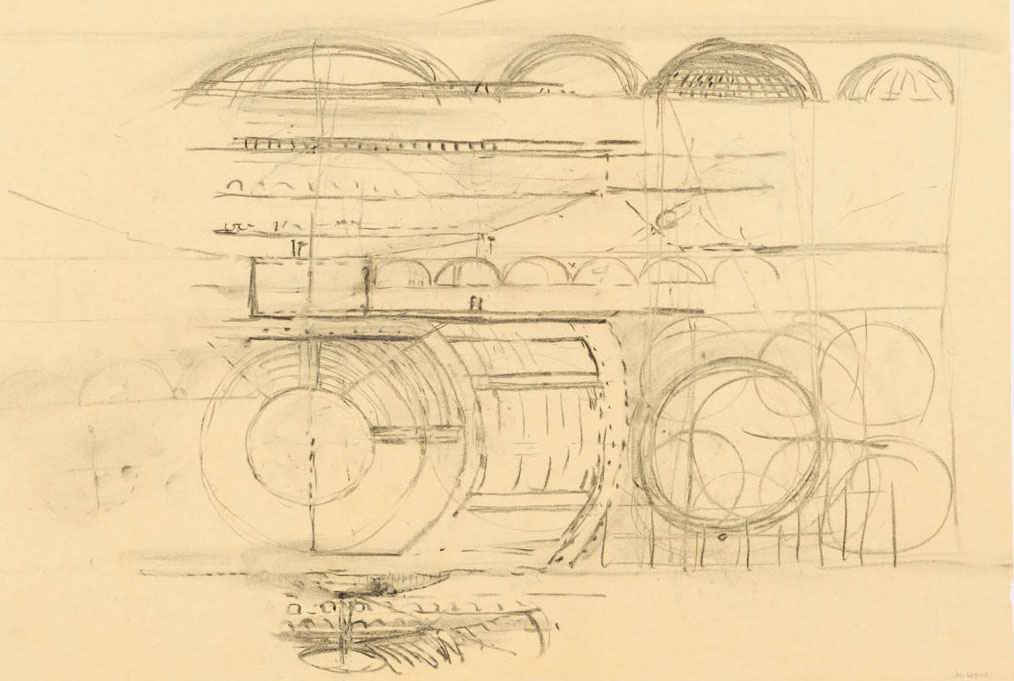

Perspective sketches for Padiglione della Biennale and Palazzo dei Congressi, Venezia, 1968/1969. Pastels e black pencil on yellow schetch paper, 57 x 64 cm. Courtesy Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal.

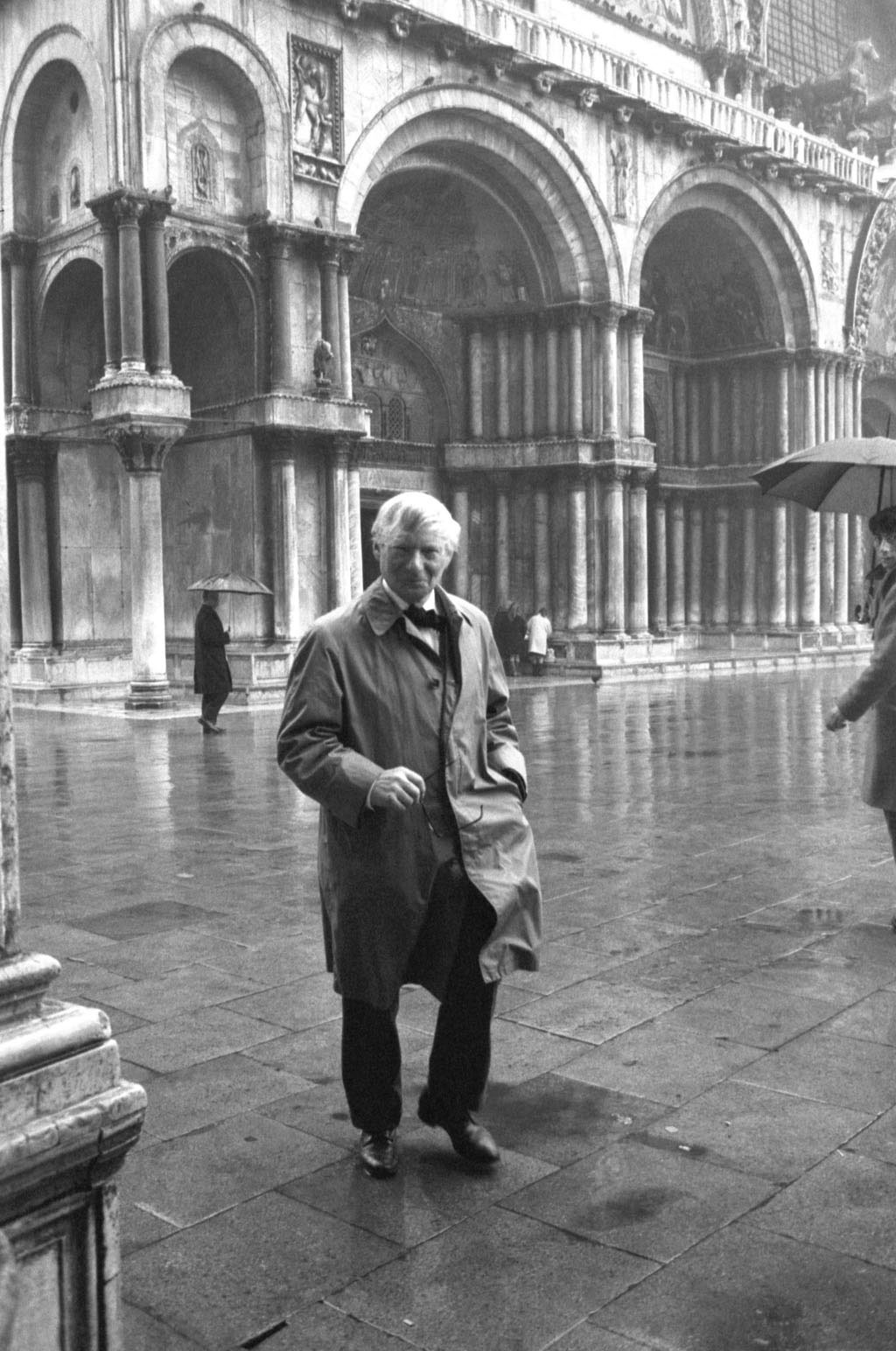

Giuseppe Mazzariol

Giuseppe Mazzariol was a Venetian art historian, professor and politician, then director of the Fondazione Querini Stampalia. Mazzariol and Kahn met in Philadelphia in 1968 to discuss the new congress palace and the foundation of a school with campuses in Venice and Florence. Louis Kahn, passionate about teaching, accepted both proposals and taught a few classes for students and professors in Venice. Both Kahn and Mazzariol shared the idea of using the new project to revitalize the city, and had full confidence in the ability of modern architecture to generate alternative ways of living. Furthermore, having the chance to build in Venice was a dream come true for Louis Kahn, while for Mazzariol it represented another way to promote his idea of the city: a crucible and meeting point for people from all over the world.

The project

The architect worked from his studio in Philadelphia, but it seems clear, given the quantity of materials he requested to a young Mario Botta (then assistant to Giuseppe Mazzariol), that he did a deep research on the working area. He strongly wanted the new building to dialogue with the main landmarks situated nearby, as Punta della Dogana, Salute church, San Marco Basilica and San Giorgio church.

The architect’s idea was to build not just one, but several buildings, each one with a separate function, as in the agora of ancient Greeks. The enclosures of the Giardini had to be removed to give a continuity to the public space, creating a dock on the Rio dei Giardini that would incorporate water into the project. The Italian Pavilion would have been replaced by an open space used to create and exhibit art.

The building dedicated to artistic creation was thought to be available during the whole year and consisted in two structures with long porches guesting ateliers and artist studios, with openings both on the new dock and on Viale dei Giardini. Two sliding bronze portals and a movable glass roof could transform the large courtyard into an internal space during the winter.

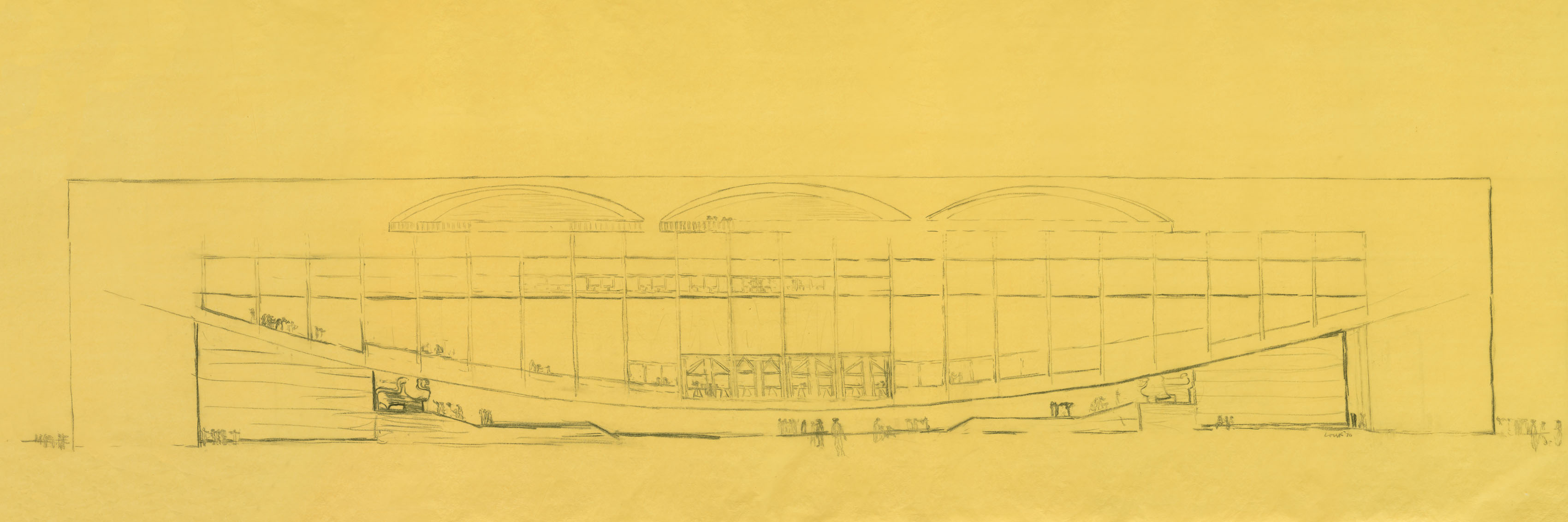

The design of Palazzo dei Congressi took inspiration from Venetian architecture, namely the five domes of Saint Mark, a symbol of the city for Kahn.

The structure of the main building recalled the ancient round-shaped theaters, consisting of concentric circles around a central stage, but shaped to fit the project area, resulting in an elongated structure under a large ballroom covered by large domes of glass.

The project was presented in 1969 in the context of a dedicated exhibition at Palazzo Ducale (Doge’s Palace), which featured drawings, three scale models and all his studies on the work area, including a wooden maquette made in Philadelphia, the actual highlight of the exhibition. In 1972 the location of the project was moved to the Arsenale area; Kahn adapted the project to the new site and continued its developing with engineer August Komendant, but it soon became clear that the local government did not really have the will to put it into practice.

The project became another unrealized opportunity to leave a mark of outstanding contemporary architecture in the fragile urban fabric of Venice.